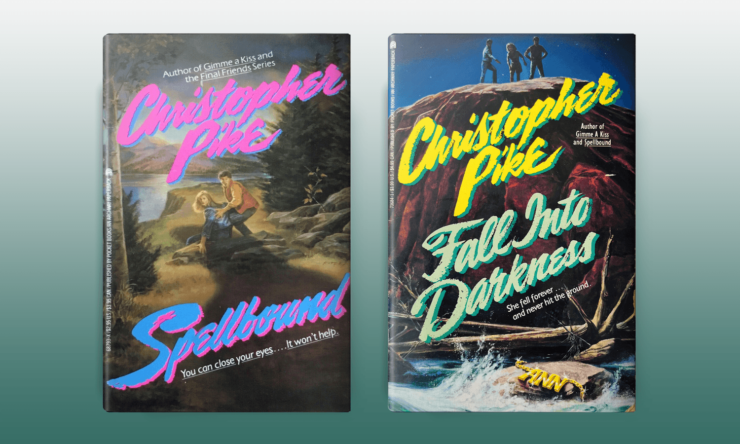

A group of teens heads out into the wilderness, chock full of sexual tension and dark secrets, and they don’t all make it back alive. What happened out there? With Spellbound (1988) and Fall Into Darkness (1990), Christopher Pike begins with this shared premise and then provides readers with two very different explanations. While Fall Into Darkness foregrounds realistic horror and Spellbound draws on the supernatural, both also reflect on how these stories get told and who gets to tell them, as lawyers and journalists try to shape the narrative of what happens to these teens, and the books become a tug-of-war over different versions of the truth.

Of these two novels, Fall Into Darkness most closely follows the 1990s teen horror formula, grounded in the complex social and romantic entanglements of its teen protagonists. Ann Rice, Sharon McKay, Chad Lear, Paul Lear, and Fred Banda head out into a local wilderness area for an overnight hiking and camping trip as Ann, Sharon, and Chad’s senior year draws to a close. Ann and Sharon have been best friends for years, even though their social positions are quite different, with Ann’s family being super-wealthy and Sharon’s just scraping by. Chad is in love with Ann and also works for her as a groundskeeper; he was also best friends with Ann’s brother Jerry, who committed suicide the previous year, supposedly because of his unrequited love for Sharon. Paul is Chad’s brother who recently moved back to the area from California following a dishonorable discharge from the military, and is engaged to Ann. Fred is a rando bar musician that Paul invited along on the overnight as a possible match for Sharon, who is a classical pianist, thinking they might hit it off because of their shared interest in music (which is apparently pretty much all the same in Paul’s mind). Sharon’s not interested in Fred, who is a crappy musician and standoffish unless he has a few beers in him; plus, she’s already got her eye on Chad, further complicating that web of attraction. Even though they’re traveling light, these young adults are heading up the mountain with a whole lot of baggage … and that’s before things get Master of Murder-level manipulative.

Like Marvin Summer in Pike’s Master of Murder (1992), Ann Rice is kind of an evil genius. She blames Sharon for her brother’s suicide, even though Jerry and Sharon only went on a couple of dates and weren’t all that serious. Ann decides that Sharon has to pay and that the best way to do this is to frame Sharon for Ann’s murder after Ann fakes her own death. She hatches a plan with Paul that includes a length of rope, a leap off a sheer cliff face, and a stolen car waiting in a nearby parking lot that will take Ann far away, where they will romantically reunite in Mexico to begin their new life together, having drinks on the beach and laughing about Sharon spending the rest of her life in prison. And it almost works: Ann and Sharon take a walk on their own after the group has set up camp. Ann tells Sharon she wants to be alone, waits until Sharon leaves, then yells “Don’t!” (82), screams, and launches herself over the edge, leaving the others to draw the conclusion that Sharon pushed her, with no witnesses able to testify to the contrary. Based on this evidence and the statements her friends provide to the police, Sharon is arrested and put on trial for murder.

The first half of Fall Into Darkness is constructed through a series of flashbacks: the prologue opens in the courtroom, with the trial interspersed with scenes from the trip. After Sharon is found not guilty (no witnesses, shadow of a doubt), Pike brings in the story of what happened to Ann after she went over the edge of the cliff, which of course, didn’t exactly go according to plan. Ann and Paul neglected to take basic physics into account, with Ann’s trajectory taking her far out from the edge before slamming her at high speed into the cliff face dozens of feet down, leaving her with a concussion and a broken arm as she attempts to free herself from the rope before Paul unties it to dispose of the evidence. Paul “misses” Ann’s tug on the rope to alert him that she’s still tethered (or intentionally ignores it—she has, after all, just written him into her will to inherit a hefty sum and despite their engagement, he’s really not that into her, but she’s rich and pretty, which is good enough) and nearly sends her falling to her death, but she gets untied just in time and makes her way down the mountain, graying in and out of consciousness from pain and exhaustion, but still committed to the plan she and Paul have laid out.

When she regains her focus and consciousness following one of those gray-outs to see Chad standing in front of her, she’s pretty sure the jig is up. And it is, but not quite in the way she thinks, because Chad figures this is the perfect opportunity for him to prove his love and win the fair maiden, telling her that Paul is only interested in her money and professing his own love. Ann remains unreceptive, however, heckling Chad and laughing in his face, a rejection to which Chad responds with homicidal rage. After all, if Ann’s already presumed dead, he doesn’t really have much to lose by actually killing her, as long as he’s fine with all of the evidence and culpability falling on Sharon (which he apparently is). Chad kills Ann, hides the body, and then resumes the search and investigation processes, taking the stand against Sharon when the time comes.

But Fall Into Darkness is like a Russian nesting doll of deception and misperceptions and there’s still even more to Chad than meets the eye: he and Sharon return to the same park for a post-trial hike, where after an odd detour through a coursing river in a pitch black cave (Sharon is terrified, which baffles Chad, who thinks this is a top-notch romantic experience), Sharon finds Ann’s now badly decomposed body and finds out the truth about that night, learns that Chad also killed Jerry and made it look like a suicide because Jerry was going tell Ann that Chad liked her, and then has to protect herself from Chad, who now wants to kill her too. Sharon and Chad have their standoff on the exact same cliff where the trouble all started and though Sharon tries to save Chad, he chooses to fall to his death, which will undoubtedly leave Sharon under suspicion of murder again, though this time she actually knows what happened and has all the pieces to support her own defense efforts.

Spellbound begins with a similar mystery: Karen Holly is killed in the mountains and the only witness to the attack is her boyfriend, Jason Whitfield. Jason says Karen was killed by a bear, but there are a lot of people who aren’t so sure. Like Fall Into Darkness, there’s a whole lot of sexual tension and secrecy as the teens try to figure out what’s really been going on. And in addition to murder and intrigue, Spellbound also has magic.

Cindy Jones is Jason’s new girlfriend, Cindy’s brother Alex is enamored with Joni Harper (a soft-spoken new girl in town, who has come from England to live with her aunt after the death of her parents), and Bala is a tall and mysterious foreign exchange student from Kenya. Spellbound has almost as much deception and intrigue as Fall Into Darkness: Alex is pretty sure that Joni likes him back (particularly after they go on a date and have a pretty intense make out session on his parents’ couch), but she also refuses to take his phone calls and goes on a date with Ray Bower, Alex’s cross country competitor and frenemy (who then ends up murdered). Jason sets Cindy up to have an accident, fall in some rapids, and nearly die, so that can play the hero and save her–right before he attempts to date rape her. When he gets her back to his house, he offers to dry her clothes and gives her a robe to wear while they wait and when he starts kissing her, Cindy decides “With her fatigue, it was easier to cooperate than resist” (98), though she does tell him to stop when he tries to untie her robe and he complies. He switches gears back to comforting her, then as she begins falling asleep, he kisses her again, with “hungry, passionate kisses, never mind that her response was almost nonexistent” (99), calling her a “tease” (100) when she tells him no again. Cindy fights him off and slaps him. When he apologizes, she decides to give him another chance and pretend like it never happened, though this assault definitely makes her see Jason in a new light, wondering for the first time if he might actually have killed Karen.

Cindy’s increasing doubts about whether or not Jason is a good guy are complicated by her growing attraction to Bala, though a contemporary reader will likely find themselves working out the ways in which this attraction may shade into potentially problematic fetishization of Bala’s otherness. Bala is peppered with questions about his background in an odd show-and-tell style format in one of his classes, where his peers marvel at the “exotic” nature of his childhood and probe for sensational stories of his shaman grandfather. Jason is threatened by Bala’s strength and masculinity, including his ability to carry Cindy back from the falls after he rescues her from the water; when the group is reunited and Jason isn’t strong enough to carry Cindy himself, he tells everyone that she can walk the rest of the way, rather than letting Bala continue to carry her. When Alex calls Joni’s aunt looking for Joni, she tells him that Joni went somewhere with Bala, confiding to him that “Between the two of us, I don’t much care for her being around that sort. She’s had trouble with them in the past” (140), a xenophobic and racist comment that refers back to Joni’s family’s missionary work in Kenya and the negative associations she seems to extend to all Kenyans, all Africans, or all Black people, depending on who all she includes under her personal umbrella of “that sort,” a distinction she does not elaborate on.

Bala reflects on his own negotiation of his cultural heritage and his desire to fit in, including his rejection of his shaman grandfather’s teaching, his refusal of magical explanations in favor of science and rationality, and his complicated relationship with animals. Animals are key figures with a great deal of agency throughout Spellbound, from Bala’s tales of the animals he has encountered in Kenya to Cindy’s aggressively protective dog Wolf. Alex has a blind parrot named Sybil who will say everyone’s name except for Cindy’s, which annoys her to no end. While the leading speculations about Karen’s murder are that she was either killed by a bear (which seems unlikely, since no one has seen any bears in the area) or a complicated murder scenario involving a rock, a rake, and an intentionally shoddy attempt to dispose of the body, Bala is the one who figures it out, bringing the missing pieces to the puzzle and having to contend with his new American friends’ rationality and disbelief. Bala apprenticed with his shaman grandfather as a young boy and one of his grandfather’s abilities was the facilitation of soul transference through intense eye contact between humans and animals, an experiment that Bala participated in many times as a child before refusing this ancestral knowledge and convincing himself that it was all a dream or hallucination. However, an instance of this transference gone horribly wrong has brought him to America, in an attempt to stop the horror Cindy and her friends now face. The truth is that Joni isn’t really Joni anymore, but rather the soul of a monstrous vulture trapped in the body of a teenage girl, murderous and hungry. Joni and her parents had come to Kenya as missionaries, where Joni became fascinated by shamanism and Bala’s grandfather’s gifts. Bala’s grandfather aided in the transference of Joni’s soul into the body of a vulture (and vice versa), but Joni panicked in the vulture’s body and flew to her parents, who shot her, leaving her soul unmoored and with no body to ground in, effectively killing her and leaving the vulture’s soul rooted in Joni’s body, which proceeded to sicken and become increasingly monstrous. Her parents took her back to England, but the vulture in Joni’s body murdered them both and her brother saw something so traumatizing that he ended up in a mental institution, with Joni sent off to her aunt in America.

Bala is horrified that his grandfather would transfer the soul of a vulture into a human body, telling Cindy that even in their own experiments throughout his childhood, “I had never gone into a vulture. You could not have forced me into one; they are disgusting creatures, always hovering about, wanting you to die, wishing they had the strength and courage to kill you” (165). When Cindy challenges Bala’s perceptions by pointing out that vultures are scavengers, he disagrees, arguing that “Vultures are predators at heart. They would kill any living creature if they could, if they had the strength Joni has, and not only for food. They are hideous beasts” (177). Joni’s recent behavior certainly seems to bear out Bala’s theory: she killed Karen and Ray, destroying their bodies and feeding on their emotional energies, and she attempts to do the same to Bala and Alex.

To save her brother’s life and stop the horror, Cindy must be able to effectively suspend her disbelief, to understand the world in a way that transcends and even refutes the strictly rational understanding by which she has previously lived her life. Many others have been unable to achieve this suspension of disbelief and have paid dearly: the spirit embodying Joni killed both of her parents, who couldn’t understand the monster she had become, and even Bala himself acknowledges that belief was an uphill battle for him, despite all he learned as a boy and has seen over the course of his life, as he talked himself into believing that Joni’s struggles were the result of a psychological affliction rather than soul transference and animalistic possession. Cindy doesn’t have a lot of time to come to terms with this new worldview and she’s woefully unprepared to face off against a monstrous creature, but with no one else able to do so and her brother’s fate uncertain, she does. The central position and agency of animals in Spellbound is important here, for while a vulture (or rather, a vulture’s soul) is the problem, animals also serve as an integral part of the solution, with Cindy’s dog knocking Joni off balance and trickery forcing the vulture’s soul into the feathery body of the blind parrot, Sybil, a containable vessel from which it will be unlikely to escape.

Buy the Book

Echo

Fall Into Darkness and Spellbound both present interesting perspectives on how a story gets told, how a series of mysterious or inexplicable events might be packaged into a narrative that strives for cohesion and closure. Fall Into Darkness is structured around the court proceedings, with what really happened in the woods distilled into what is presumed to be an objective account through witness questioning and testimony. In this case, the construction of the narrative is doubly complicated, because not only does such testimony strip the events of their complexity and contradictions, but in this case, two of the witnesses (Paul and Chad) are intentionally lying, telling a story that they know isn’t true. In Spellbound, the attempt to create a logical narrative from complex and illogical occurrences comes through a series of newspaper articles by investigative reporter Kent Cooke, who digs into the details of the mysterious deaths, though he never even comes close to the truth. In both of these novels, the attempt to construct a narrative, to turn the events into a story, is fundamentally flawed: there are questions that can’t be effectively answered, mysteries that can’t really be solved. There are no tidy explanations and there’s no clear resolution. While many of the answers are unpacked in Fall Into Darkness, the reality itself remains unbelievable to some people (including the police officer who verbally abuses Sharon as he arrests her for the second time). In Spellbound, there are simply no logical answers that can be provided, as the horrors transcend and refute how most people understand the reality of the world around them, and there is no story that can be built around these events that will ever be wholly satisfying for many of those who seek answers.

This is further complicated by who gets to tell these stories and impose this narrative structure: in Fall Into Darkness, a good part of the story is constructed by Sharon’s lawyer, Johnny Richmond, who is super sleazy and takes on the cases of young women in trouble with the goal of having sex with them after he’s secured them a not guilty verdict (which apparently works an appalling amount of the time, if Sharon’s fellow inmates are to be believed). He secures Sharon’s freedom by constructing a narrative that doesn’t really reflect the complexities of who she is or what she has endured, and he doesn’t really care about the veracity of the story he’s telling, just the end result of her not guilty verdict and the chance to make a pass at her (he does, at a post-trial lunch, and while Sharon’s mother is weirdly in favor of this arrangement, Sharon herself refuses him and later, decides she’d better get a different lawyer for her second anticipated murder trial). In Spellbound, Kent Cooke is working hard to figure out what happened to Karen, Ray, and later Joni, investigating and presenting his findings in a series of local newspaper articles that he hopes will shed some light on what really happened. He seems more invested in uncovering the actual truth than Johnny Richmond, but like so many others in the novel, he is incapable of seeing what that truth really is, instead digging his heels in and focusing on proving what he believes to be Jason’s culpability, suspecting a financially and politically motivated cover up. In the end, both of these men’s attempts to construct a cohesive narrative fall short: Johnny Richmond’s story only scratches the surface of what actually happened and the truths Sharon uncovers, while Cindy explicitly refuses Cooke’s attempts to tell her story or the stories of her friends.

Fall Into Darkness and Spellbound highlight the strength and style of Pike’s work, which runs the gamut from realism (Master of Murder, Fall Into Darkness, The Midnight Club) to supernatural and even cosmic horror (Spellbound, the Last Vampire series, the Chain Letter duology). Beginning with a similar premise—the mysterious death of a young woman in the wilderness—Pike gives us two very different explanations, taking us there by two very different routes. Both in the comparison of these two novels and taken as a whole, Pike’s fiction continually reminds readers that there is horror to be found everywhere, in internal and interpersonal conflict, as well as from inexplicable and supernatural sources. There is no singular way to see the world, no one explanation that precludes and disproves all others.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.